Australia has long experienced the drastic effects of climate change. In 2006 and 2007 specifically, Australia experienced heat waves and was at the height of getting by the infamous millennial drought period. Therefore climate change became part of the political agenda of Australia, with the independent Garnaut Climate Change Review that is commissioned by the Australian state recognising it being in the nation’s national interest to take more decisive action to reduce carbon emissions. Subsequently, the government looked into reducing carbon emissions as early as 2011, even before the Sustainable Development Goals 2030 Agenda took place. While a carbon pricing scheme, therefore, existed in the country since 2011, it was unfortunately repealed on July 1st 2014, by a new government. However, with the heightened need to be mindful of carbon emissions, Australia has been on the verge of reintroducing a new carbon pricing scheme. This article will give an overview of the government’s efforts at introducing a carbon pricing scheme and where the new scheme would be strictly enacted.

Why Carbon Emissions Particularly?

It should be noted that while Australia only accounted for 1.5 per cent of global greenhouse gasses (GHG) emissions, it is one of the 15 top emitters and has one of the highest per capita emissions in the world. While it is widely known that the population of Australia is set to increase in the future, the rate of growth is said to be much higher than most developed countries sparking concerns about GHG emissions rising in the future. For a long time, Australia has been contending about whether a carbon pricing scheme should be introduced. For instance, in 2007, under Former Labour Prime Minister Kevin Rudd, a Carbon Pollution Reduction Scheme (CRPS) was introduced to parliament, which failed. The failure was due to the resistance posed by emissions-intensive trade-exposed industries, specifically coal which Australia heavily relied on economically, as China received the largest share of natural resource exports. They argue that the only way for Australia to benefit economically and environmentally is by waiting until a carbon price scheme is introduced to Australia’s competitors in the coal, steel, petroleum and mining sectors.

The Carbon Pricing Scheme in 2011-2014

Given the concerns raised in the previous section, it may be wondered how the carbon price scheme in 2011-14 did come about. The Gillard Labor minority government introduced the Clean Energy Act 2011, which came into effect a year after, on July 1st 2012. This became possible due to a particular political situation in which elections in August 2010 resulted in a hung parliament requiring the support of one green and three independent members of parliament to form a government. These members joined Julia Gillard’s Labour Party on the condition that a carbon price was implemented. Hence, in September 2010, a Multi-Party Climate Change Committee was introduced, which was responsible for drafting and carrying out the passing of the Clean Energy Act. This was also followed by the introduction of the Renewable Energy Target (RET), the Carbon Energy Finance Cooperation (CEFC) and the Australian Renewable Energy Arena (ARENA).

The pricing scheme introduced through the Clean Energy Act applied to Australia’s biggest carbon emitters, whereby a pricing mechanism was introduced that put a price on Australia’s carbon pollution. This also meant that this law did not apply to most companies in Australia, nor did it include households. In considering what kind of companies then had to abide by this regulation, it included entities that had one or more facilities that emitted one emission of 25,000 tonnes of carbon dioxide in a financial year and companies that supplied natural gas or manufactured, imported, or produced liquefied petroleum gas or liquefied natural gas for non-transport use in a financial year. Hence, considering the inflation projections, such companies were liable to pay a fixed price with a rise of 2.5 per cent for three years annually. At the starting point, the fixed price was AUD 23, which increased by the time 2014 came due to inflation to AUD 25. The companies included those responsible for 60 per cent of carbon emissions in Australia, including players in the wastewater, stationary energy, electricity and related sectors. The carbon price’s revenue was then used to ease costs for households and industry. It was incorporated to establish centres that caused renewable power or make similar investments that looked at low-carbon alternatives.

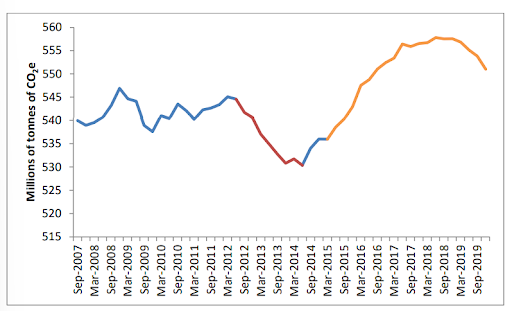

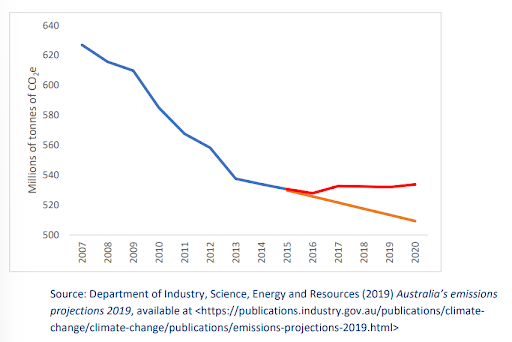

A 2019 publication by the Department of Industry, Science and Resources notes that Australia experienced a significant reduction in GHG emissions from 2013 to 2014.

The Cap and Trade Program in 2015 - 2018

The Australian government next transitioned to a cap-and-trade program in 2015, with the Liberal National Party announcing climate change policies and committing to an Emissions Trading Scheme through an Emissions Reduction Fund. This included a price cap and a price floor. Companies that produced over 100,000 tonnes of GHG emissions were liable for this program. The core goals of this program were to reduce GHG emissions by five per cent less than 2000 levels by 2020, gain over 50 per cent of revenue generated from the carbon price and provide it to low-income households through tax relief and family benefits payments. Companies can purchase any amount of permits which gives them the right to emit 1 tonne of greenhouse gases which costs exorbitant amounts for the organisations. However, this was ineffective compared to the previous system since it incentivised companies to embark on emissions reduction projects. The fund, moreover, has received broad contention for failing to sign up essential players. As a result, after 2014, emissions increased again.

Proof That A Carbon Pricing Scheme Can Reduce GHG Emissions

Since the payment scheme came to halt in 2014, Australia lost an effective mode of reducing emissions. For instance, the following graph demonstrates in orange how much emissions would have been reduced if the act was not repealed, whereas the red line presents the rate of emissions that increased from the progress the country experienced until 2014-15.

While the emissions have comparatively decreased from the high levels existing before 2013, the graph presents how much potential the pricing scheme would have had in reducing GHG emissions if not repealed. The only reason the emissions, however, did continue to reduce is attributed to the continuation of RET, CEFC and ARENA that the Labour government introduced with the carbon price. Although these three policies were also meant to be abolished, they received significant opposition in the Senate and thus have to date, reduced more than 334 million tonnes CO2e.

What Environmental Friendly Policies Are Existing Today?

All states in Australia have to date, announced their aim to reduce net-zero emissions by 2050. Hence, climate change legislation is said to be making a comeback in the Australian parliament. This is because global carbon pricing schemes are now also gaining momentum. Additionally, surprisingly investors and emitters are now demanding such a scheme to be introduced to ensure they are given a fair chance to continue doing business in the industry. Hence, around 20 per cent of GHG emissions are now coveted by a pricing scheme, with the world’s largest economies implementing carbon pricing initiatives. Australia, which already had a tried and tested carbon pricing scheme, could be a step ahead of others if reimplemented properly. This does not mean it will be easy for Australia to continue a carbon pricing scheme if significant opposition or disinformation campaigns that led to the fall of the original scheme happen again.

Australia has been working on introducing a carbon price for each industry, known as the safeguard mechanism, a form of baseline and credit scheme. This is expected to come into place in July 2023, although negotiations to perfect the scheme are still ongoing. Under this scheme, however, Australia’s big polluting sites will be required to reduce GHG emissions by nearly 5 per cent annually until 2030.

The news scheme puts a price on approximately 30 per cent of Australia’s GHG emissions and applies to 215 of the largest GHG emitters in Australia. The scheme, however, excludes the electricity generation sector and instead focuses on gas extraction and coal mines, steel, aluminium, cement and related sectors. In this sense, the new scheme covers a smaller share of the economy than the original scheme introduced from 2012 to 2014, which in contrast, did include the electricity sector. However, the trading price of emission credits is set to be more, capped at AUD 75 a ton, which may rise over time. Hence, the ultimate objective is to keep the price higher to have a more substantial financial incentive to cut emissions and adopt low-emissions processors and assets. One significant difference between the older schemes and the present ones is that there is no source of revenue for the government.

One loophole, however, is that there are no limits on using carbon offsets for industrial emitters. Hence, representing the Greens, Mehreen Farqi notes that industries like coal and gas should not be allowed to buy their way out of real pollution cuts. It, therefore, remains to be seen the developments that will be made in this regard later this year.